WASTE INSTEAD OF HONEY

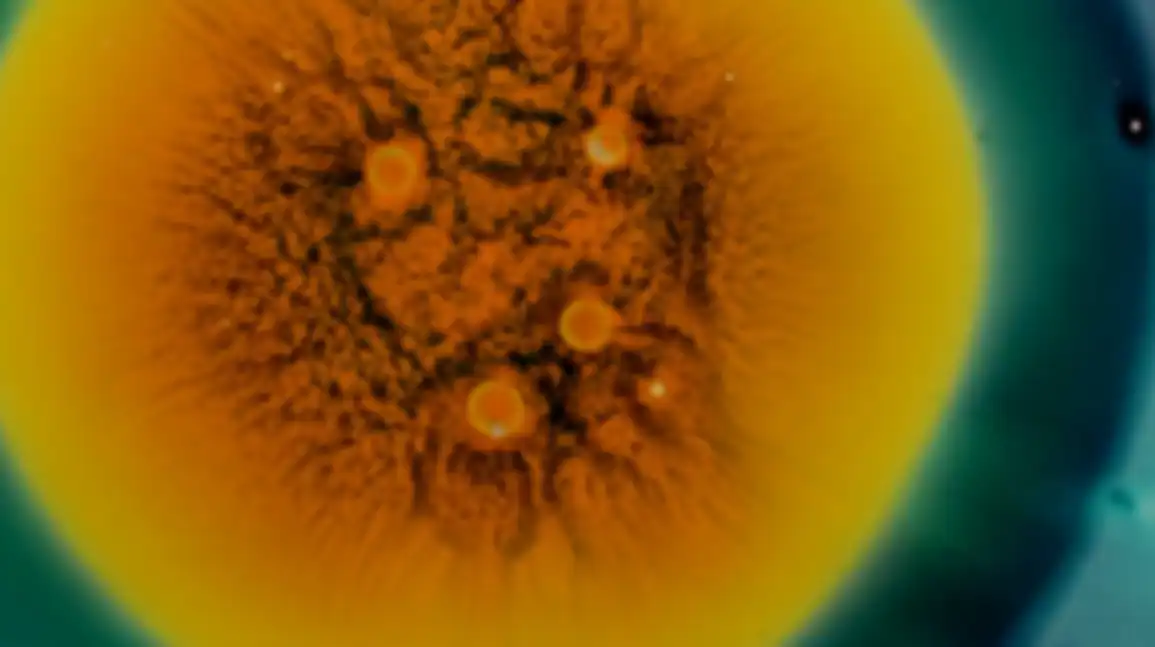

How AmphiStar uses microbes to produce biosurfactants

Your Challenge:

Circular Biomanufacturing

Until now, our manufacturing processes have almost entirely been based on the use of newly, mined raw materials with not enough coming from the recycling of waste streams. This places an enormous burden on the environment and our society. In addition, dependencies remain in global supply chains that could be reduced through access to local materials.

Instead, we can create a circular economy in which new products are manufactured locally, using valorized waste streams as a source for raw materials, to build more sustainable and resilient production platforms.

To achieve this, biomanufacturing processes must be developed to market maturity and directly integrated with modern production processes. Scientific advances in recent years have produced new findings and methods that can significantly increase the performance of biomanufacturing processes and open up new application possibilities. Although alternative ways of producing a wide range of products to replace the conventional petrochemical or chemical manufacturing processes have gone to market, breakthroughs have so far only been achieved in niche applications. We need to reach the goal where the majority of bulk products are made through biomanufacturing processes that enable the use of locally available raw materials.

00:00

The prototype must demonstrate how carbonaceous waste streams can be processed and fed to microbes as food. The overall bioproduction process shall not use E. Coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae and shall demonstrate continuous production over a period of at least 180 days during the Challenge. At the end of the process, at least three different products should be produced using a modern manufacturing process, such as additive manufacturing.

The Challenge started in November 2023 and runs over a three-year period. A panel of globally recognized experts assisted SPRIND in evaluating the applications and selected the participating teams. During the Challenge period, teams further develop their bioproduction technology to achieve the Challenge goal.

Teams participating in this Challenge are fully challenged. SPRIND therefore provides intensive and individual support. In order to unleash the full potential, SPRIND provides a coach to accompany each team's work, advise them and network them. After one year and after two years, the jury reconvened in each case to evaluate the interim status and decided which approaches have the greatest breakthrough innovation potential and which teams can prove themselves in the Challenge until the end.

In October 2025, the expert jury selected the participants for the third stage of the Circular Biomanufacturing Challenge. Over the next twelve months, five teams will each receive up to €2.5 million to further develop their technology. The teams will also be supported and advised by SPRIND and connected with other experts and coaches. At the end of the year, a decision will be made as to which teams will win the challenge.

Science Youtuber Jacob Beautemps introduces the Challenge teams at Breaking Lab

Please feel free to contact us at challenge@sprind.org.

More about this topic

More Challenges and Funken